Ask the Experts: What are ultra-processed foods and how do they impact our health?

Three UC Davis experts answer your questions to provide insight based on research

Diet. Just the word alone can trigger an uneasy feeling and heated discussions with seemingly endless flavors of recommendations. Over the years, Americans have shifted in our general approach to food based on evolving guidance. In the span of a few decades we have gone from the “eat less fat, cholesterol and salt” model to a heightened focus on reducing sugar consumption, and most recently towards eating more natural foods and avoiding those that are heavily processed.

Now we are hearing a lot about ultra-processed foods.

Many are confused, wondering what we should do and who we can trust.

A rapid sequence of actions added fuel to the discussion and concerns. Leading up to the national election of 2024, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., now the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, raised concerns on the links between ultra-processed foods and chronic diseases. California Governor Newsom confirmed it to be a bipartisan issue with an order to ban several food additives. Soon after, the FDA banned red dye No. 3 from foods.

The rapid nature of this conversation and actions are raising a lot of questions and concerns.

To help clear up the confusion, we reached out to UC Davis experts in nutrition and food science, asking them to provide some clarity based on research.

Listen to the Podcast: The Science and Politics in Processed Foods

The term “ultra-processed” is new to many of us. Can you explain what it means and how it differs from other processed foods?

Charlotte Biltekoff: Ultra-processed foods (UPFs) refers to foods that are comprised of industrially produced ingredients and created through a series of industrial techniques and processes. It is a narrower and more specific category than “processed food,” which doesn’t have a clear meaning. Critics tend to argue that all processed food is bad and should be avoided, while advocates tend to argue that all food is processed, so attacking processed food is nonsensical.

The “ultra-processed” category was developed in 2009 by a group of Brazilian public health researchers led by Carlos Monteiro, as part of a classification system called NOVA that groups foods by extent and purpose of processing. The four categories are:

- Unprocessed and minimally processed foods, those we would think of as whole foods such as meat, produce and eggs.

- Processed culinary ingredients, or those used to prepare whole foods such as butter, oils and spices.

- Processed foods, or those foods made through combining the previous two groups and processing through preservation or cooking.

- Ultra-processed foods, or those made of industrially produced ingredients non-existent or rare in culinary use and created through a series of industrial processes. Includes soft drinks, many packaged snacks, mass produced breads and pastries, flavored yogurts, and instant soups.

It is helpful to keep in mind that the category was not designed to classify individual foods. The goal of the NOVA classification system is to provide a tool researchers can use to understand the health impacts of dietary patterns that include high percentages of ultra processed food.

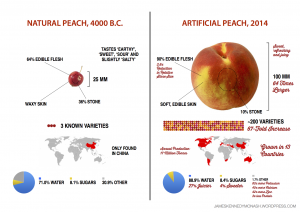

James Kennedy’s “Artificial vs. Natural Peach” captures the dilemma of “natural” vs. “artificial” terminology. Courtesy of James Kennedy: https://jameskennedymonash.wordpress.com/2014/07/09/artificial-vs-natural-peach/

Are there “good” and “bad” processed foods?

Charlotte Biltekoff: Thinking about “good” and “bad” food in terms of processing, rather than nutrients, challenges the nutritional classifications that have long shaped dietary advice in the US (and elsewhere), such as MyPlate, which focuses on food groups and does not take processing into consideration at all. Many countries now use NOVA as the basis for dietary guidelines, including Brazil and France. In the process of determining the 2025 dietary guidelines for Americans the USDA has considered addressing processing, but appears not to be moving forward with any processing-related recommendations.

Nitin Nitin: Classification of “good” and “bad” processed foods is challenging as there have been limited studies that have demonstrated a causation relationship between processed foods and health. Although NOVA and several other classification approaches use association studies that link dietary choices with the incidence of chronic diseases at a population level, these studies do not establish scientifically rigorous guidelines for “good” and “bad” processed foods. One common theme that has emerged is the association of high sugar, high lipid, and foods with certain additives, such as artificial colors, with negative health impacts for individuals over a relatively long consumption period. To keep this classification of “good” and “bad” food choices in perspective, having a cake, chocolate or fries occasionally may not be a “bad” choice.

What does research show in terms of the links to health-related diseases?

Angela Zivkovic: The vast majority of research on ultra-processed foods (UPFs) has been observational in nature, where people are asked to report on what they eat and then scientists take that information and apply statistical analysis techniques to explore associations with various health outcomes. It is important to note that these types of studies can show an association, but not causation. Nearly all of the studies on UPFs out of more than 20,000 are observational studies. These studies generally report an association between the intake of UPFs and obesity, cardiovascular health, some cancers, depression and gastrointestinal disorders. However, it is critical to understand that these studies simply report an association between what people remember and report eating through an instrument called a food frequency questionnaire, and the disease outcome in question. We have no way of telling whether the association between the reported intake of UPFs and the disease outcome is due to the intake of UPFs or whether it is a reflection of an overall diet and lifestyle. For example, it is possible that people who eat more UPFs also drink more sugar-sweetened beverages, or are less active, or eat less fruits and vegetables.

Very few studies that can actually evaluate the direct impacts of UPFs have been performed. The common finding in the handful of intervention studies that are available is higher consumption of calories and weight gain for participants assigned to a diet with UPFs even when the foods offered were matched for total content of carbohydrates, protein, fat and fiber. These studies tell us that there is something about UPFs that makes us eat more total calories and that including UPFs in the diet will likely lead to weight gain.

There are several key aspects about UPFs that we should all keep in mind. First, in general, UPFs are nutrient-poor, calorie-dense, very tasty/appealing or all of the above. Nutrient-poor foods are those that basically for every calorie of that food that you eat you get very little in the way of nutrients (protein, vitamins, minerals, fiber, etc.). This is a problem because when you eat these foods you have consumed calories but not any of the rest of what you need to be getting out of your food to sustain all of the various processes that the body needs to perform. When foods are calorie-dense and particularly tasty it is easy to overeat and end up consuming more calories per day than you need. Doing this consistently over time will lead to weight gain. So consuming UPFs has two main problems, one being that we can more easily overconsume calories and thus gain weight, but also that we may be missing the nutrients that we would be getting if we were instead consuming nutrient-dense whole foods like fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, eggs, yogurt, chicken and fish.

Nitin Nitin: Although some association studies and a few intervention studies with a small group of participants attributing the health impacts of UPFs exist, there is a lack of understanding as to how the ingredients and formulation of the food contribute to health impacts compared to processing food with specific technologies. The ingredients and formulation of the food may include sugar, oils, emulsifiers, and preservatives. Processing technologies may include ovens, homogenizers, mixers and extruders, and high-pressure or thermal pasteurization. The combination of ingredients and processing technologies define the food structure and properties, and the potential nutritional profile based on the digestibility of the food and absorption of micro and macronutrients. Often in UPFs, various refined ingredients such as simple sugars and oils are combined with other ingredients such as starches, gums, and color additives with the aid of processing technologies. Thus, to understand the impact of UPFs on health, the effects of processing and ingredients need to be evaluated both individually and in combination to develop a robust framework for developing foods with improved nutrition and potential beneficial impacts on health.

Are the links to diseases direct or indirect (via obesity or metabolic disorders)?

Angela Zivkovic: It is likely that the links between UPF consumption and disease outcomes are both indirect and direct. It is likely that both the excess calories consumed leading to weight gain and metabolic disorders and the lack of nutrients (vitamins, minerals, polyphenols, etc.) together contribute to the increased risk for a variety of diseases. It is also possible that certain ingredients in UPFs are particularly harmful in some individuals and groups. For example, the various artificial colors, flavors, stabilizers and preservatives used in many UPFs may also play a significant role in increasing disease risk, and this may be particularly the case for children, in whom the doses of these ingredients per pound of body weight are higher than in adults.

However, it is also important to point out that if one eats, say, one snack-size bag of chips with artificial flavors and colors once a month or less, it is extremely unlikely that these types of ingredients would have any negative health effects. On the other hand, if one eats a one-pound bag of the same chips twice a day every day, now we are talking about potentially serious doses of these chemicals that may have a chance to accumulate and have measurable negative health effects. The dose makes the poison.

How do ultra-processed foods influence the gut microbiome?

Angela Zivkovic: There is little evidence from intervention studies and the only data that we really have are observational data. For any observations that have been found of an association between the intake of UPFs and negative outcomes related to the gut microbiome, we simply don’t know at this point how much of the problem can be attributed to consuming these foods vs. how much of the problem is due to not consuming healthy foods high in fiber and polyphenols, which are known to be beneficial for gut health.

Do ultra-processed foods affect people differently?

Angela Zivkovic: We really just don’t have the answers to any of these questions yet. As mentioned previously, all we really have is tens of thousands of observational studies and reviews of those observational studies. What these tell us is that in those groups of individuals who consume large amounts of UPFs there is a slew of negative health associations. However, it is likely that all this points to more of a cultural and socio-economic problem more than differences between susceptibility to the effects of these foods between different groups of individuals.

I am personally fascinated by the fact that in the US today eating these UPFs has been normalized. It is now completely normal to see kids eating a bag of flavored chips and even candy as a “snack” at school. At the college level I see students eating pizza and burgers and fries from a fast-food restaurant as a “normal lunch.” Families eat out at fast food restaurants or other convenience locations as a “normal dinner.” These all used to be exceptions not the rule. American culture has drastically changed over the last several decades from one where home-prepared meals were normal and these convenience foods were a “special exception” or “special treat” to one where cooking at home is considered a hassle and many people consume UPFs for the sake of convenience, and perhaps even cost. I think it is a mistake to blame the UPFs themselves for the health problems they can cause. It is not these foods that are the problem it is their overconsumption and acceptance as normal foods that is at the heart of the problem, in my opinion. The problem with blaming the foods themselves is that it will only prompt the food industry to reformulate and it is not clear that this reformulation will lead to better outcomes. Instead, it appears to me that we need to fundamentally change our culture around food and in fact our perceptions about what is “food” vs. what is “edible entertainment.”

Food is supposed to “nourish” us, which means it needs to be delivering all the nutrients we need, from protein, carbohydrates, fiber and fat, to all the vitamins, minerals, and various other food components like polyphenols, that are known to be needed for a variety of metabolic and physiologic functions. It is not just a matter of adding these individual pieces to individual foods either because food companies cannot predict or control how much of any one product an individual might eat in a day. For example, I have some serious concerns about all of the various nutrient-boosted drinks out there. If people are drinking five vitamin-boosted waters per day they may be getting way too much niacin, for example, which was recently found to be associated with negative effects on vascular function when consumed in excess of the Recommended Daily Allowance. I am fascinated to hear Charlotte’s perspective on all of this as someone who thinks much more carefully about the relationships between culture and food.

Sources estimate that on average, diets in the U.S. are comprised of around 60-70 percent ultra processed foods. Why have we reached such high levels in the U.S.?

Charlotte Biltekoff: I completely agree with Angela that solving dietary health problems through product reformulations misunderstands the problem. The very definition of ultra- processed food points to the reasons why they are so widely consumed:

“Processes and ingredients used for the manufacture of ultra-processed foods are designed to create highly profitable products (low-cost ingredients, long shelf-life, powerfully branded). Their convenience (imperishable, ready-to-consume), hyper-palatability, and ownership by transnational corporations using pervasive advertising and promotion, give ultra-processed foods enormous market advantages. They are therefore liable to displace all other NOVA food groups, and to replace freshly made regular meals and dishes, with snacking anytime, anywhere.”

Product formulation may introduce more natural sounding ingredients, rearrange ingredients in new ways, or market products toward growing concerns about ultra processed food, but it does nothing to address the underlying reasons why ultra processed foods are so prevalent. At the same time, it doesn’t make sense to blame individuals for having diets so heavy in ultra processed foods; eating habits are shaped by their environments and UPFs are cheap, accessible, heavily marketed (including in schools and college campuses) and designed to be delicious, if not addictive. According to NOVA, that is, precisely what makes them ultra-processed food!

Instead, we need to understand the systems and structures that shape our current food system. We have a farm subsidy system which has made corn and soy cheap to grow, a regulatory system that allows food companies to essentially self-govern the introduction of new additives and places very few limits on marketing, and market forces that require food companies to constantly deliver growth and profits. Changing the level of UPF in American diets will have to include regulatory and policy changes, not just product reformulation or dietary advice and education.

What explains the difference between ingredients used in food products in European countries vs. the United States?

Charlotte Biltekoff: Europeans have long adopted the precautionary principle, which means that additives must be proven safe before they can be included in food. U.S. food regulators have been unwilling to adopt this model, even though they have been pressed by consumer groups to do so. Instead, U.S. food regulation is shaped by a “proof of harm” model that speeds innovation and supports business interests by making it much easier to introduce new ingredients, while placing the burden of navigating a potentially unsafe food environment on consumers — mainly women — a point made convincingly by Norah MacKendrick in her book, Better Safe than Sorry, which also provides a thorough overview of US food regulation and its history.

Another difference in the U.S. may be attributable to what is commonly referred to as the Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) loophole. GRAS was originally intended to allow processors to bypass formal FDA review of new additives that were generally recognized as safe, such as spices, salt, and yeast. In 1997 the FDA – facing a backlog of applications for new additives – made a change to the rules that opened the floodgates and basically sidelined the more stringent process. In the new process companies only needed to notify the FDA after making their own safety assessment. Companies were supposed to adhere to guidelines for making those assessments, but they were nonbinding, and the agency provided no oversight regarding the qualifications of those enlisted to conduct the reviews. A 2011 report on food additives by the Pew Charitable Trust found that a third or more of the ten thousand chemicals that could be put in food were never formally reviewed by the FDA. GRAS has been in the news lately, because Health and Human Services Secretary Robert .F Kennedy Jr. – who oversees the FDA – has said that he wants to eliminate the loophole.

What are the factors that drive manufacturers to use certain ingredients or processes?

Charlotte Biltekoff: Product development is a complex negotiation between the pragmatics of what is possible (materially and economically) and the pressures of consumer preferences, or trends. Since the early years of the 21st century food companies have been trying to develop and market products to appeal to consumer who want “real” food. As I write about in my new book, public attitudes toward processed foods have become increasingly negative due to a confluence of legitimate concerns about health, sustainability, regulatory laxity, and the appropriation of scientific authority by the food industry. Products that are labelled “natural,” have short ingredients with only words you can pronounce, or are covered in “free from” claims may appeal to consumers, but they cannot address the larger concerns about food, the food industry, and the food system that have shaped the idea that good food is “real.”

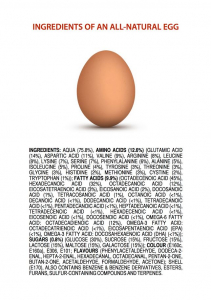

James Kennedy’s illustration to erode the fear that many people have of “chemicals”, and demonstrate that nature evolves compounds, mechanisms and structures far more complicated and unpredictable than anything we can produce in the lab. Courtesy of James Kennedy: https://jameskennedymonash.wordpress.com/2013/12/12/ingredients-of-an-all-natural-banana/

How would you describe the role of trust between consumers, regulators, food growers, manufacturers and health care providers?

Charlotte Biltekoff: The food industry recognizes that consumer trust is waning and sees this as a problem manufacturers must address, particularly if they want to continue to operate with minimal restrictions or regulatory hurdles. The work of building trust with consumers has largely been taken on by trade associations, such as the International Food Information Council (IFIC), and “front groups” (i.e. those working on behalf of industry while claiming to be impartial) such as the Center for Food Integrity. For example, IFIC started an organization called the Alliance to Feed the Future that developed a curriculum for K-8 grades promoting the benefits of “modern food processing” and processed foods. Concerned that traditional, facts-focused efforts like these are no longer working, the Center for Food Integrity develops and disseminates new models based on “transparency” and “shared values.” My research suggests that all of these efforts fail to address the underlying questions and concerns of the public, which have to do not just with health and safety but also the aims and trajectory of the food system itself, and the power dynamics that shape the kinds of questions that seem reasonable to ask about food as well as the kind of expertise that is deemed relevant to answering questions about food.

What role have advancements in food technology and processing played in addressing key issues like food availability, safety, nutritional needs or environmental sustainability?

Nitin Nitin: Advancements in food technology and processing have played a vital role in enabling the development of safe food products with high nutritional quality and desired shelf life to improve food availability. Pasteurization technologies, including heat or high pressure (cold-pressed), significantly contribute to several nutritious food products’ safety and shelf life, including infant foods, fruit, vegetable- and dairy-based food products, and beverages. Drying and freezing technologies, including spray drying, vacuum microwave drying, and individual quick freezing, play a key role in preserving foods and enhancing the availability and maintaining the nutritional properties of several seasonal food products. Furthermore, food packaging technologies, including barrier films and modified environment packaging, have significantly contributed to extending the shelf life, maintaining the nutritional properties of diverse food products, and reducing food waste.

Recent advances in food processing technologies to enhance environmental sustainability include significant efforts to electrify various heating and drying technologies. Examples include microwave and ohmic heating for pasteurization and sterilization of food products and ultrasound and microwave-assisted drying applications. Multiple technologies, including advanced heat pump technologies, are actively explored in research and industrial operations to capture waste heat from food processing operations.

How are technological advances changing the landscape of ultra-processed foods?

Nitin Nitin: Ingredient formulations play a significant role in the classification of foods as ultra-processed food products. Many of these ingredient formulations are selected to create specific textures or structures, for example, the use of emulsifiers and stabilizers to stabilize dispersed oil in water systems or enhance the mouthfeel of the food products. Similarly, food ingredient formulations may include preservatives to maintain the shelf life and nutrient content of foods. In certain products, the selection of specific artificial colors may be based on the requirements to maintain the color of products during the heating or cooking of foods.

Based on technological advances, novel structuring or texturization processes may be developed to reduce the requirements of emulsifiers and stabilizer ingredients in food products. Similarly. advances in both food packaging and processing technologies may reduce the reliance on preservatives to maintain the shelf life and nutritional properties of food. Furthermore, advances in food chemistry and processing may enable the selection and stabilization of natural colors in food products.

In addition, the current classification approaches for ultra-processed foods have not clearly described the role of the ingredient formulations and processing technologies in impacting the nutritional and health aspects of food. Research is needed to clearly understand the individual roles of ingredient formulations and processing in influencing food properties and their impact on human health.

In what ways might artificial intelligence play a role in the food processing system moving forward?

Nitin Nitin: Digital information about food systems and their analysis with AI models are expected to play a significant role in advancing food processing systems. These roles may include AI-enabled digital twin technologies for enhancing consistency and efficiency in food production. Similarly, advances in AI-assisted bio-analytical technologies will improve food safety and the quality of food products, as well as reduce the cost of implementing regulatory requirements. AI-enabled analysis of food systems, including food by-products, may significantly enable us to improve the sustainability of food systems, recovery of vital nutrients from food by-products and reduce food waste. Similarly, AI-enabled analysis of food composition and structure and their integration with food digestion is expected to improve the nutritional and health impacts of food. Thus, the applications of AI in food systems are expected to connect food growers, manufacturers, consumers, researchers, and medical professionals and result in improved food safety and nutrition and reduce food waste.

Affiliated Research Units

UC Davis Innovation Institute for Food and Health

UC Davis’s Innovation Institute for Food and Health (IIFH) fosters impactful partnerships with food companies, investors, entrepreneurs, and researchers. Through these strategic industry-academic collaborations they drive interdisciplinary research and accelerate the commercialization of innovative technologies, addressing global challenges in food and health. IIFH is a unique catalyst designed to enable industry to leverage the world-class research and innovation capabilities within UC Davis.

Additional Information

Media Contacts

AJ Cheline, Director of Marketing and Communications for the Office of Research

Marissa Pickard, Strategic Marketing Manager, UC Davis Innovation Institute for Food and Health