Pakistani Researcher Hopes to Improve Conditions for Women Working in Agriculture

By Lisa Howard

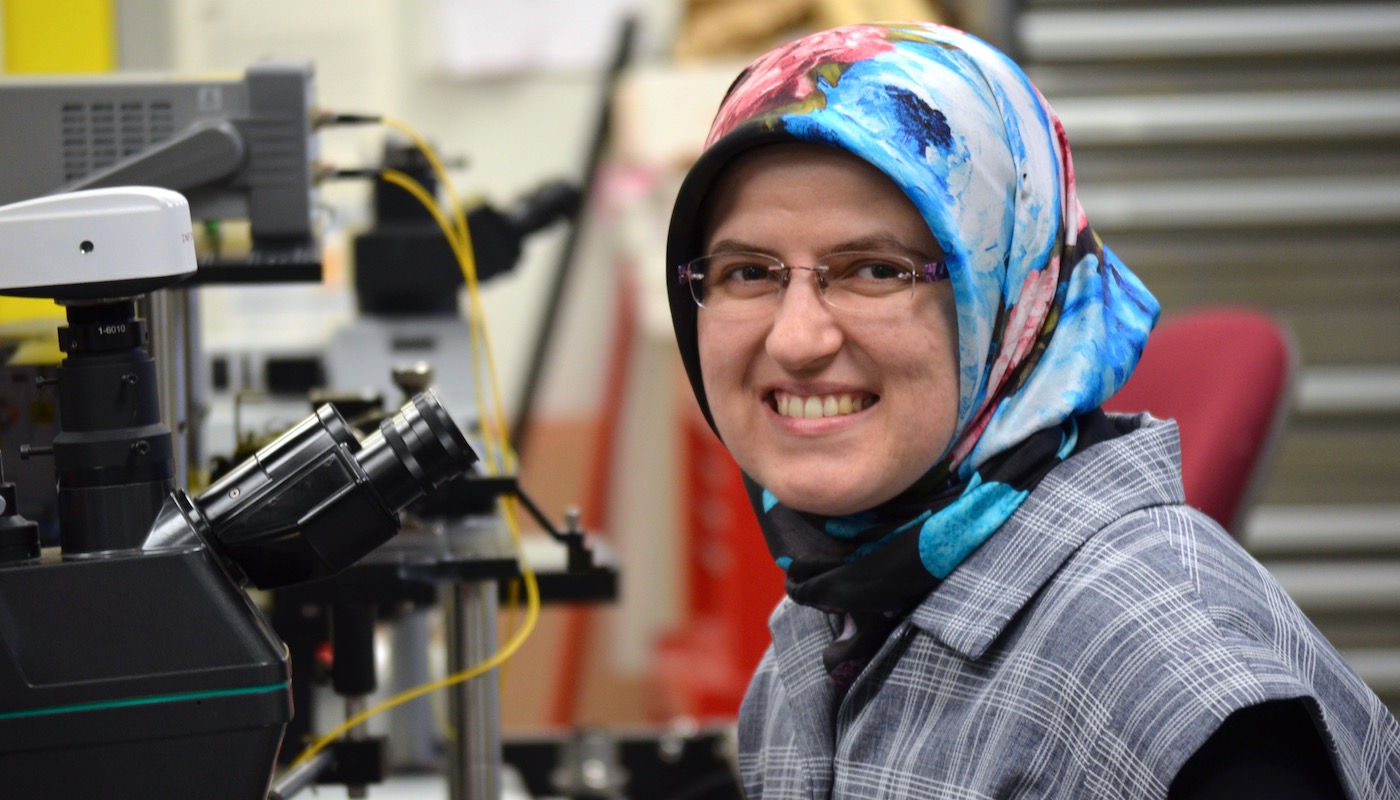

The women Rukhshanda Abdur Rehman has interviewed in her native Pakistan have put a lot of faith in her. They are the agricultural workers who plant, tend and harvest the region’s wheat and rice crops, among others, in the agriculturally rich region of Punjab.

“After I talk to them, they feel like they are an important part of our society,” said Rukhshanda. “They told me, ‘You are the only one who has chosen this field, and who has given us time.’”

Rukhshanda is a Ph.D. candidate in applied psychology at the Lahore College for Women University, oneof the oldest female institutions in Pakistan. The focus of her dissertation is sexual harassment of agricultural workers in Pakistan. Since October 2018, she has been an international student at UC Davis, doing research at the Western Center for Agricultural Health and Safety at the invitation of Karen Bales, a professor in the UC Davis Department of Psychology, and Kent Pinkerton, director of WCAHS.

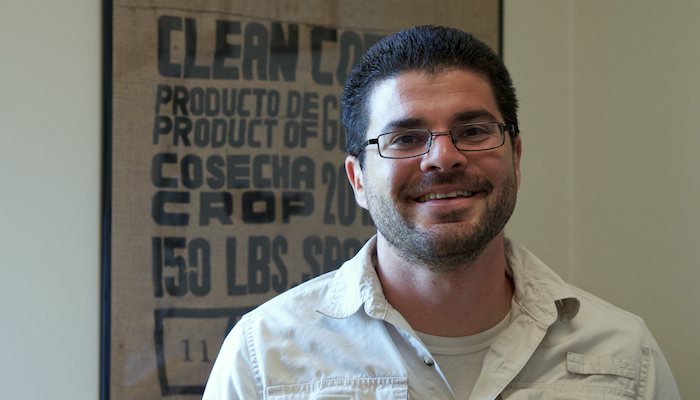

“Rukhshanda’s research on sexual harassment in the agricultural workplace in Pakistan parallels ongoing research we are conducting in our center on sexual harassment in the agricultural workplace in California,” said Pinkerton. “As Rukhshanda has learned from us, we also have learned from her. Her research provides us with the opportunity to compare and contrast worker issues faced in Pakistan and the United States.”

Studying issues of sexual harassment is relatively new in her country. “I’m one of the first Pakistani psychologists who is doing work on sexual harassment in the agriculture sector. It’s a very sensitive issue and topic.” To gain the trust of the women she interviewed, she spent a lot of time with the farmworkers. “I made the environment confidential. And they gave me confidential answers.”

Although her focus is sexual harassment, she also bears witness to what their lives are like. “Many are extremely poor,” said Rukhshanda. “After giving birth, many women go back to working in the rice fields with their babies when the babies are still very small — two or three months old. The water is dirty and has snakes. They are in the sun and heat all day. There is no medical facility. They can get infections. I say to them, ‘you need to stay home.’ But they tell me ‘if I do not do something for my children, I will go home without food. And sleep without any food.’”

Their plight — and her desire to improve it — is what drives Rukhshanda to document their experiences.

Agriculture in Pakistan

Agriculture makes up the largest sector of Pakistan’s economy. About 42 percent of Pakistan’s labor force works in agriculture, which contributes about 24 percent to the country’s gross domestic product. Important crops include wheat, cotton, rice, sugarcane and maize as well as pulses, onions, potatoes, chilies and tomatoes.

According to a 2015 report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 72 percent of the total female labor force in Pakistan work in the agriculture sector. Unlike California agriculture, where much of the labor depends on seasonal and migrant farm workers, many of the women spend most of their lives in one village, working for one landlord.

The Pakistani system of land ownership and laborers has been compared to feudalism, where powerful landowners have tremendous control over local laborers.

“Lands are transferred generation to generation,” Rukhshanda explained. Her father is a landowner who grows wheat and rice in Wahndo, near the city of Gujranwala. “My grandfather transferred land to my father and then he takes care of it.” She said her uncle also works in the agriculture sector.

In the rural village where she grew up, Rukhshanda notes that many girls only receive a primary-school education. Rukhshanda attended primary, middle and high school at the Government Girls High School Wahndo. For college she attended the Government Postgraduate College for Women, Satellite Town, Gujranwala. For graduate school she movedto the city of Lahore. At Lahore College for Women University she obtained a master’s degreein Health Psychologybefore pursuing her Ph.D.

In her graduate classes, she was often the only student to have come from a rural village, which sometimes made it difficult for her. But her teachers were encouraging and her habit of closely observing people made psychology an easy fit. One of her mentors gave her direction: “She said, ‘you need to do something for your area.’”

Her parents were supportive of her continued education even though it meant she spent time away from her family. “My mother is educated and she motivated me. My father is also educated and he fully supported me in my studies.” Her father is also happy with what she is pursing now. “We need to do something for our farmworkers. So this is the reason I start my study and observe which types of problems farmworkers — especially women — are facing.”

Her husband is also supportive. The couple married in Pakistan before she moved to Yuba City, which is where her husband is from. “He has own trucking business but he has a degree in criminal justice law, so he knows the value of education.” She said that even though he is busy with his business, when she is doing research at UC Davis he drives her from Yuba City and then picks her up. They recently had their first child.

Learning about the labor practices in California — and the history of the farmworker movement — has been eye-opening for her.

“We have labor law and laws against sexual harassment but we have little application of the laws. There is more oversight and enforcement in California.” She explained that there is no platform or mechanism to even register a complaint in Pakistan, something she’d like to see changed. “Farmworkers are unaware of their rights. They don’t know the laws about harassment.”

She hopes the research she’s conducting will begin a conversation, but she is realistic. “It will be a time-taking process,” said Rukhshanda. After she finishes her dissertation, she plans to present her work at other universities and conferences, and also hopes to work with the regional directors of the agricultural sectors to draw attention to what is needed to improve the conditions for agricultural workers.

She clearly values the support she received from the women she has interviewed and feels a tremendous responsibility to help them. “Every farmworker is feeling herself as a ‘blessing lady.’ They are very positive about my work and very hopeful. They are also waiting for me.”

Contact

- Kara Schilli, Communications Specialist,. Western Center for Agricultural Health and Safety, [email protected], 530-752-5585

- Kent E. Pinkerton, Director, Center for Health and the Environment, [email protected], 530-752 8334

Resources

- Western Center for Agricultural Health and Safety

- WCAHS: Sexual Harassment Prevention