Research Shows Deporting Immigrants Hurts Local Economies

By Lisa Howard

During the early days of the Great Depression, when many Americans were desperate to find jobs, state and local officials in the United States began forcibly repatriating Mexicans, including American citizens of Mexican descent, to Mexico.

Jobs were scarce — unemployment would eventually reach 25 percent in 1933 — and the thinking was that removing Mexicans would make more jobs available for Americans.

Between 1929 and 1935, hundreds of thousands of Mexicans left the United States. Some estimates put the number at 500,000. Francisco Balderrama, author of Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s, puts it at over a million.

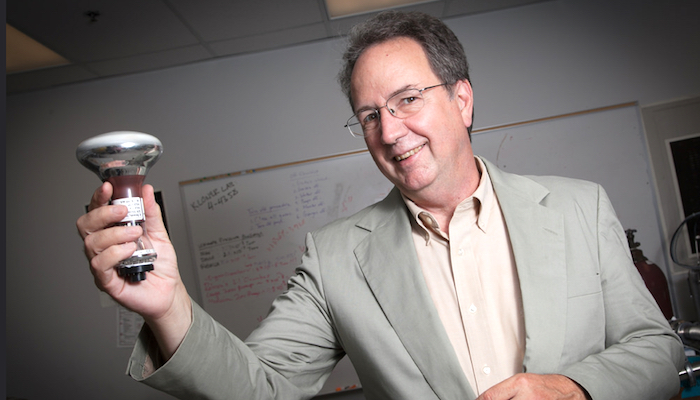

Professor Giovanni Peri, the chair of the Department of Economics at UC Davis, was intrigued by this relatively forgotten episode in American history.

Much of Peri’s career has been spent analyzing the impact of immigration on labor markets and local economies — and more generally, looking at the economic determinants and consequences of international migrations. Peri was curious. Did the jobs left behind by Mexicans end up being filled by Americans? Did the forced repatriation improve the economy?

Peri teamed up with Jongkwan Lee, a research fellow at the Korea Development Institute, and Vasil Yasenov, a postdoctoral scholar at UC Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy, to study the data. He had been the Ph.D. advisor for both economists at UC Davis. Their working paper, “The Employment Effects of Mexican Repatriations: Evidence from the 1930s,” was published in fall 2017.

“We looked systematically at how these repatriations affected local economies,” Peri said. “What was the job growth for American cities in the subsequent decade? What were the wages? How did they change? And what type of jobs did Americans get as a consequence of the Mexican repatriation?”

Contrary to what the U.S. officials had expected to happen, the researchers found no evidence that the employment of Americans grew faster (or declined slower) in cities and counties where a large number of Mexicans had been removed or left.

“If anything,” Peri said, “there is evidence of the opposite. Communities where a large number of Mexicans were repatriated tended to suffer more job losses and had less employment growth for American workers.”

Peri explained that the Mexican population at that time was particularly specialized in jobs as laborers and farm laborers, what he refers to as “manual workers at the bottom of the wage distribution.” When that group left, few Americans took those jobs and the losses ended up creating a domino effect.

“Jobs connected to these lower-level jobs disappeared as well. Farms need laborers, but they also need workers like craftsmen who make tools. If a farmer can’t get his fruit picked, he doesn’t need to buy boxes,” Peri said.

The same was true in manufacturing. “Factories had laborers, but they also had clerks, accountants, craftspeople and managers. When you take away a bunch of laborers, you can create a negative multiplier effect. A few of them, yes, became laborers. But most of them just lost their jobs because firms closed or relocated,” Peri said.

A historic photo by Dorothea Lange showing Mexicans picking cantaloupes at 6 a.m. in Imperial Valley, California, May 1937. Although the intent of Mexican repatriation was to create more jobs for Americans, a UC Davis study shows most native-born workers didn’t take the jobs left behind by Mexican laborers. (Credit: Dorothea Lange, Farm Security Administration, Library of Congress)

The Migration Research Cluster

In addition to being a professor and chairing the department, Peri is also the director of the Migration Research Cluster, an interdisciplinary network of UC Davis economists, sociologists, political scientists, historians, demographers and law scholars working on issues related to international migrants and migration.

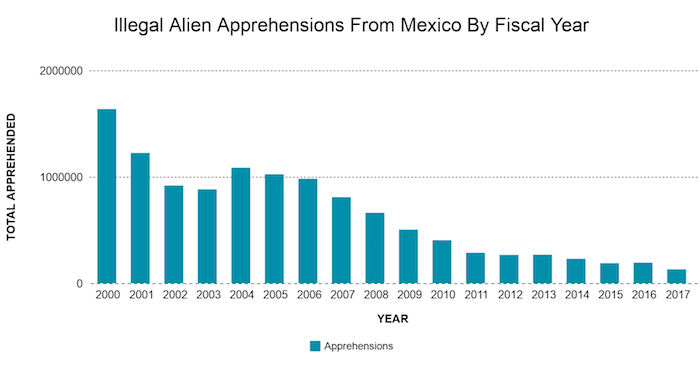

Studies from the interdisciplinary researchers in the Migration Research Cluster often reveal data that go against popular narratives — such as the current perception that hordes of Mexicans are crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. In the past few months, attention has been focused on Central Americans crossing the southern border to request asylum, but this ignores a 10-year trend that shows a significant decline in Mexican and Central American populations arriving in the U.S.

Consider a 2016 paper from Diane Charlton, now at Montana State University, and J. Edward Taylor, a professor of agricultural and resource economics at UC Davis, both associates of the Migration Research Cluster. Their research found the number of Mexican farm laborers from rural Mexico — the primary source of hired workers for U.S. farms — declined by 150,000 workers every year between 1980 and 2010. The result has meant farmworker shortages, with far-reaching implications for farmers, farm labor organizers, rural communities and agricultural workers.

Erin Hamilton, an associate professor of sociology at UC Davis who is also affiliated with the Migration Research Cluster, presented analysis at the annual Population Association of America meeting in April 2018 that showed over the past decade, migration from Mexico to the U.S. has reversed. The research estimates that half a million U.S.–born children have moved to Mexico between 2000 and 2015. A Pew Research study from 2015 found similar results, showing that after the Great Recession, more Mexicans were returning to Mexico than were entering the U.S., creating a reverse immigration flow.

These researchers try to make sure migration, and data and ideas about managing migration, get noticed. They also engage and train graduate and undergraduate students in analyzing migration and migrants from a variety of perspectives.

“There are many different aspects to it, but generally the Migration Research Cluster focuses on quantitative, high-quality, policy-relevant research,” Peri said.

“We talk to the media, policymakers, other ‘think tanks’ and institutions that are trying to share information and facts that are important for people to know,” Peri said. “I am continuously motivated by thinking, ‘What can we tell people? How can we make a difference in the policies and in the community?’ I think migration is a very important topic, and I am fortunate to be at UC Davis doing this,” Peri said.

There has been a steady decline in the number of undocumented immigrants from Mexico apprehended by U.S. Customs and Border Protection since 2000. During fiscal year 2000 (Oct. 1–Sept. 30), U.S. Customs and Border Protection apprehended 1,636,883 illegal aliens from Mexico. In 2017, they apprehended 130,454. (Source data: U.S. Customs and Border Protection)

Immigrants as Economic Assets

Peri himself is an immigrant to the United States. He grew up in Perugia, Italy, and after graduating from Bocconi University in Milan, spent a year doing volunteer work helping newly arrived immigrants who were mostly from North Africa and Eastern Europe.

This was in the early 1990s, and at the time, Peri said, Italian newspapers were “ramping up fear, saying that Italy was being invaded by immigrants.” He had become friends with several of the immigrants he worked with, and Peri saw something completely different: how incredibly motivated they were. He thought they would become a tremendous economic asset for Italy.

“I was fascinated by how economists often overlooked the contributions of immigrants. I thought this would be a very interesting area of research.” Peri went on to do graduate work in exactly that, and studied economics at Bocconi University in Milan, and then later at UC Berkeley, where he received a Ph.D.

“Immigration is a huge social, global issue, but if we start looking at the economic aspect of it, a lot of people will be more convinced by facts,” Peri said.

Professor Giovanni Peri, the chair of the UC Davis Department of Economics, is also the director of the Migration Research Cluster, an interdisciplinary network of UC Davis economists, sociologists, political scientists, historians, demographers and law scholars working on issues related to international migrants and migration. (Lisa Howard/UC Davis)

Immigrant Impact on Alabama’s Poultry Industry

In 2017, in addition to his usual research, Peri also completed a study for the popular NPR radio program This American Life, hosted by Ira Glass.

Glass asked Peri to research whether an influx of immigrants into Albertville, Alabama, during the 1990s and 2000s had taken away poultry jobs from Americans and driven down wages for American workers. It was for a two-part segment by Glass and Miki Meek called “Our Town.”

Poultry is the biggest agribusiness in Alabama, making up 10 percent of Alabama’s economy. During the 1970s and 1980s, the poultry plants in Albertville employed a lot of Americans. The town was also mostly white (for instance, in 1990 Albertville was 98 percent white). Twenty years later, in 2010, it was more than 25 percent Latino.

When the immigrants arrived in Albertville and began working in the poultry plants, wages didn’t grow. Hourly wages for workers no longer kept up with the cost of inflation. For the people who lived in Albertville, and for politicians in the state, the obvious reason for the wage stagnation was that the immigrants, many of whom were undocumented, were keeping wages down. There was also the perception that the immigrants were taking jobs away from native-born workers.

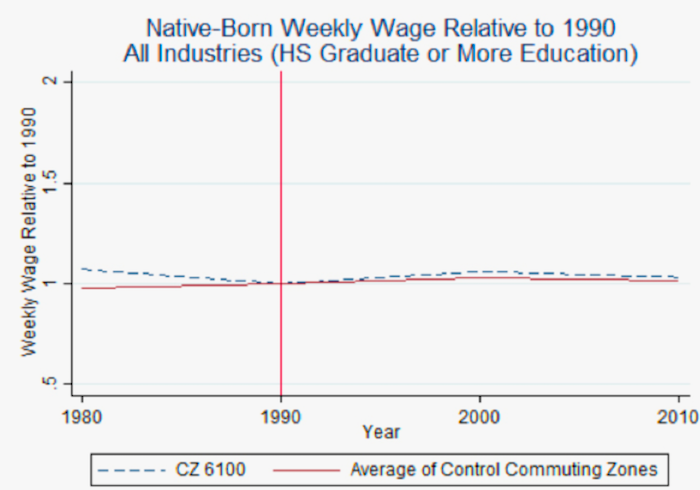

For his research for This American Life, Peri used census data from 1980, 1990, 2000 and 2010 and compared Albertville to similar labor markets in Alabama that didn’t experience a large influx of immigrants, that didn’t go from 98 percent white to 25 percent Latino.

“I tracked the cities that looked the most like Albertville in labor force characteristics and employment performance up to 1990. We found there was not very much difference in the employment and unemployment levels for people with low education between Albertville and elsewhere after 1990 when many immigrants arrived,” Peri said. “Native-born workers did not seem to have been displaced by this inflow of immigrants in Albertville.”

Wages for native-born workers in the Albertville area who had a high school education or above were on par with the wages in other regions in Alabama that did not have an influx of immigrants, indicating the influx of immigrants did not drive down wages for most workers. (Peri and Wiltshire study for This American Life)

He also found that wages generally weren’t worse than elsewhere. Workers without a high school diploma, which were about 10 percent of the population, may have seen at most a 7 percent drop in salary due to the arrival of the immigrants in Albertville. But Peri pointed out, “All workers with low levels of education during these 30 years did not do well.” His research found that other workers — those with a high school diploma or above — either saw no change or actually saw an improvement by a few percentage points.

“If you look at what was happening with the wages and employment, they were declining in Albertville and everywhere else in Alabama because this was also the period of mechanization and outsourcing of some jobs. Minimum wages weren’t growing much. Unionization was shrinking. All of these causes went into creating a slow decline in the wage,” Peri said.

One thing the influx of immigrants did do, however, was significantly grow the size of Albertville’s economy. About 6,000 new Latino residents moved to Albertville and, in addition to being workers, they were also consumers. They needed places to live, and haircuts and groceries and gas for their cars. Their jobs at the poultry plants were fueling other businesses — other jobs in town — and were also helping preserve the poultry plants and their respective administrative, clerical and connected jobs.

None of that, though, seemed to change the perception that immigrants drove down wages and took jobs away from native-born workers.

“They see immigrants coming, they see the low wages and unemployment, and they think the immigrants are the reason,” Peri said. “But this is a much larger national trend, one that has affected wage inequality all over the United States. But these national trends — driven by mechanization, globalization and institutional choices — are harder to pinpoint locally. Immigrants are easier to see and to identify as those you think responsible for your problem.”

The data from Peri’s studies have been consistent. “Local economies thrive and grow on a multiplicity of jobs. More immigrant jobs actually help create more American jobs, not the other way around,” Peri said.

Media Contacts

- Lisa Howard, UC Davis Office of Research, 530-752-8117, [email protected]

- Giovanni Peri, UC Davis Department of Economics, 530-754-0515, [email protected]

Resources

- The Employment Effects of Mexican Repatriations: Evidence from the 1930s

- This American Life, “Our Town”

- Analysis of Marshall-DeKalb area, relative to similar labor markets in Alabama, 1980–2010

- UC Davis Migration Research Cluster

- A Declining Farm Workforce: Analysis of Panel Data from Rural Mexico

- Giovanni Peri, Professor and Chair, UC Davis Department of Economics

- STEM Workers, H-1B Visas and Productivity in U.S. Cities

Latest News & Events